I attended a conference session called, “Defusing the Power of Toxic Religion for Sexual Advocacy,” because I’m writing a memoir about intersections of faith, family, and feminism in my life and of my experience with black female sexuality within the context of the Southern Black Church. And because Rev. Beverly Dale, who I had heard some time ago on the Unscrewed podcast, was facilitating the workshop.

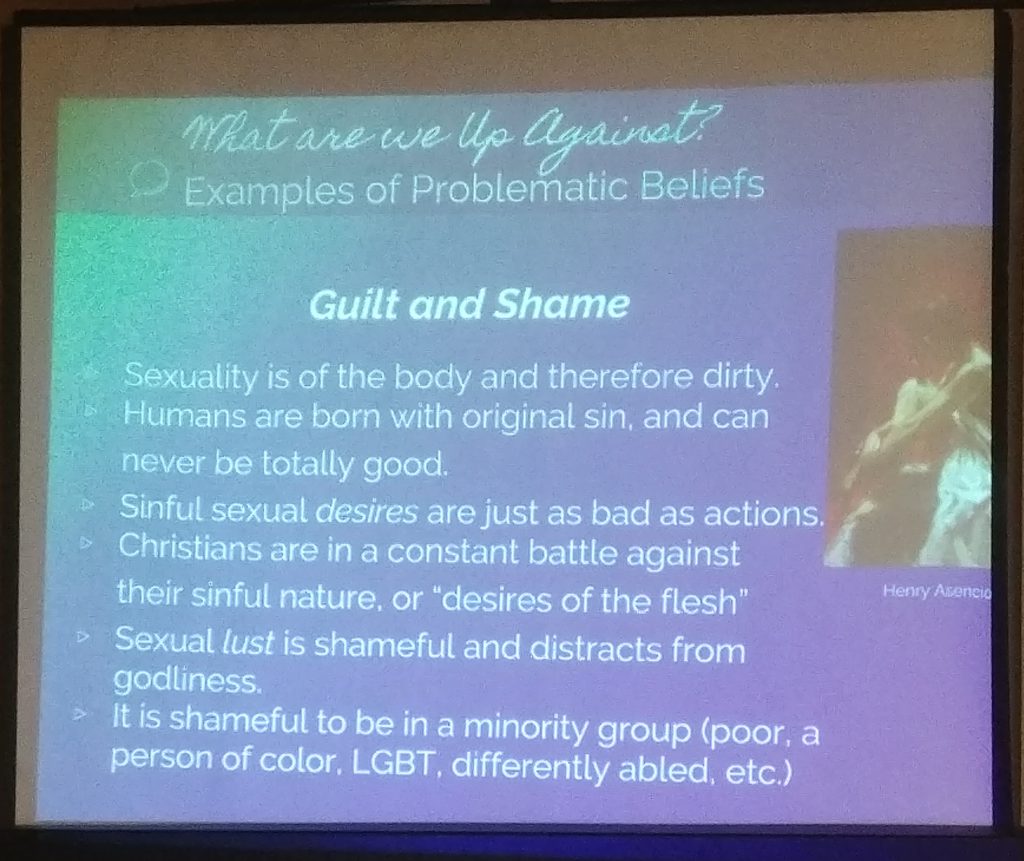

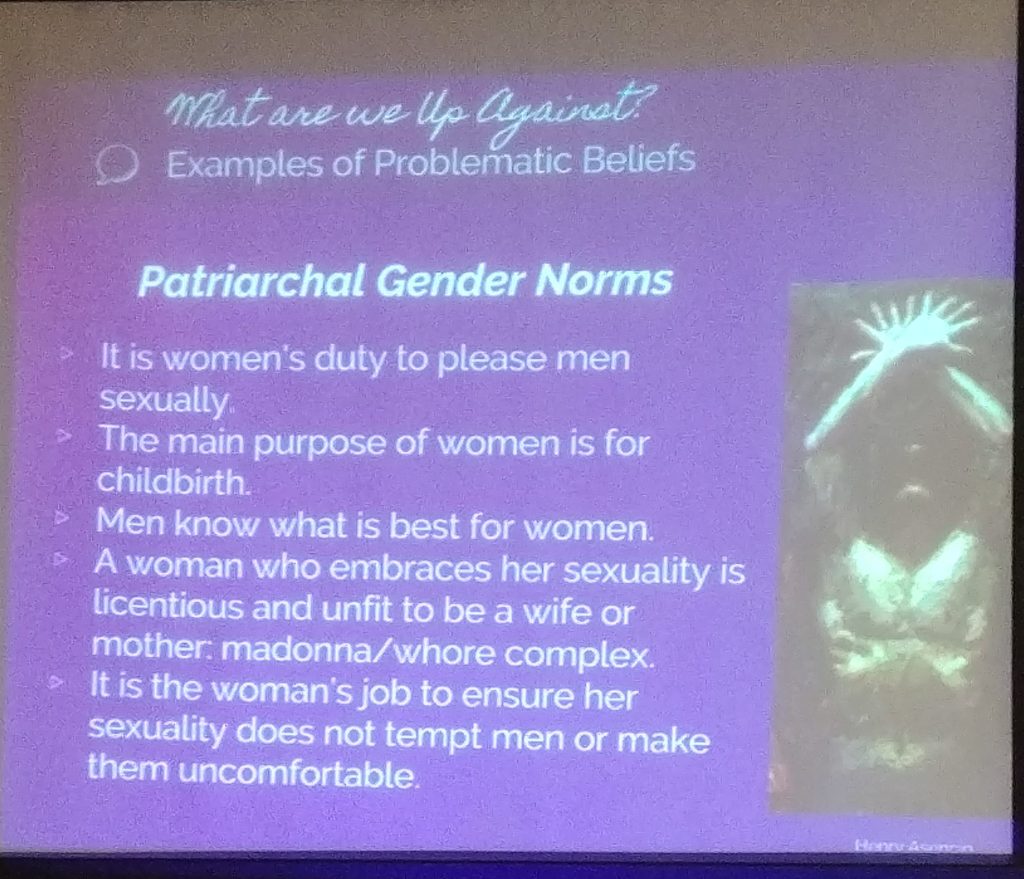

In the introductions, we heard common experiences: religions had taught us our bodies were evil, sex was wrong unless done one certain way, only men were supposed to have sex or enjoy it, desire was something to be afraid of, hell was waiting for us, etc., and we carried shame and guilt with us into our intimate relationships. And then there were the experiences of those who had a religious or non-religious upbringing that affirmed their sexuality. They attended the session because they’re sex therapists and want to understand their clients better, or because they want to be in dialogue with people who have had the opposite experience.

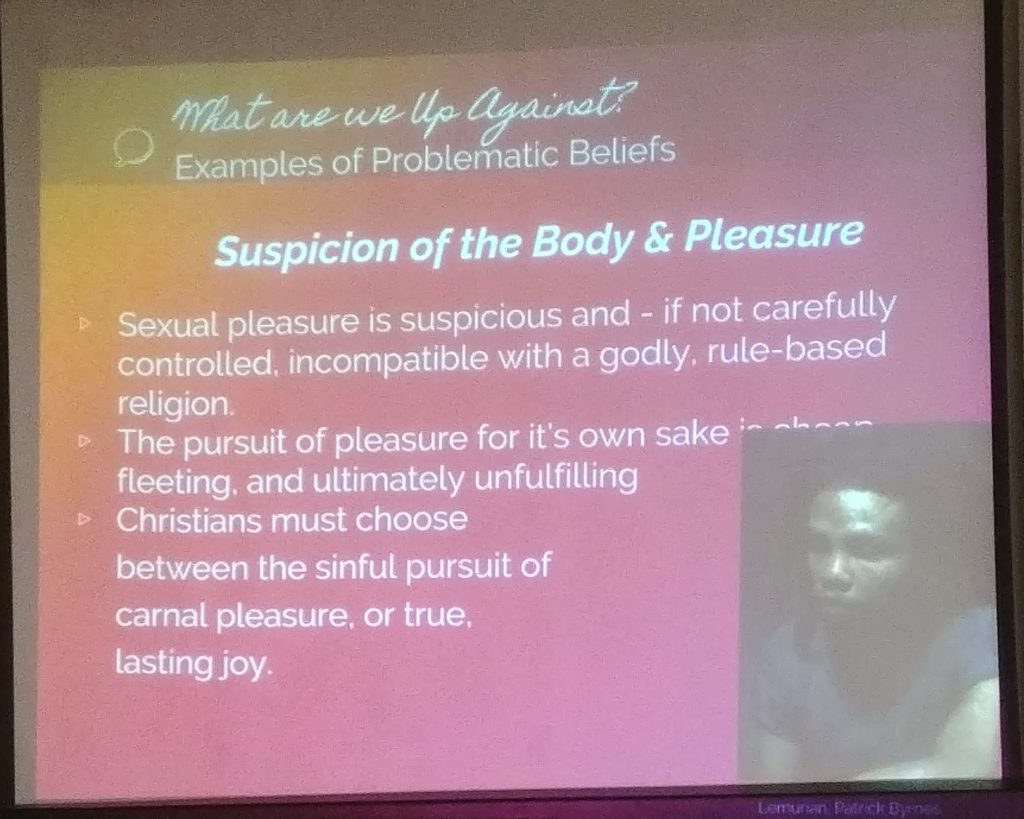

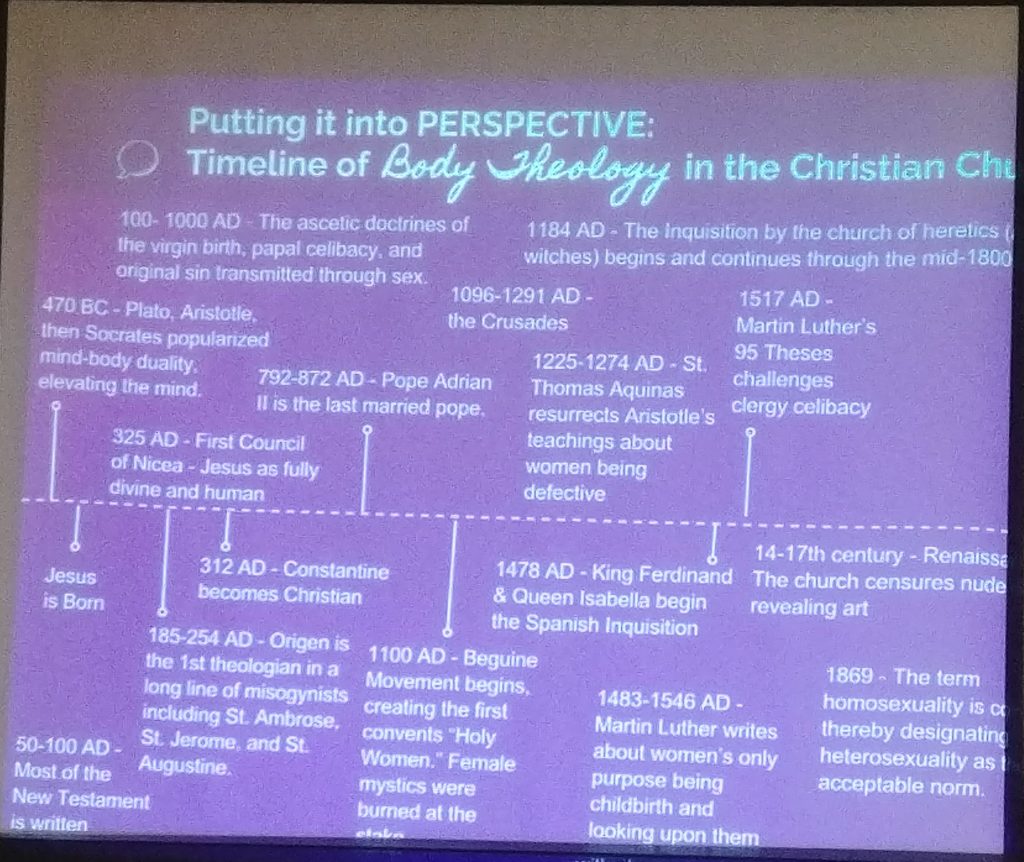

Rev. Bev and her colleagues, Rev. Lacete Cross and Rachel Keller, guided us in some approaches to undoing the power those teachings have held over us and affirming the positive. (The issue of shamed sexuality isn’t exclusive to Christians, as another session centering the experiences of Muslims would prove, but Christianity is the presenters’ area of expertise, so that’s the religion I’ll be talking about.) First, we were presented with a timeline of sexual thought in the Christian church.

Rev. Bev made this remarkable statement:

“Augustine and Jerome were incredible writers. Whoever controls the pen controls history, and these men wrote out of guilt and shame. We call these folks church fathers and then saints. They were good Christians in many ways, but not when it comes to the body, women, or sex.”

The men who wrote church doctrine had a debilitative foundation, but what about the Bible? The words therein are supposed to be God’s and therefore timeless to Christians. In that case, twenty-first century followers and readers have the tools to reframe the text.

By going from embedded theology (i.e., the same morality tales you learned over and over again and accept) to deliberative theology (reflecting on what we’ve learned from those same old stories and considering alternative meanings), the Bible becomes a different book, sometimes even a liberating one.

One of the examples Rev. Cross used was that of Ruth, Naomi, and Boaz. The story most of us have been taught is as follows (if you know it, skip to the next paragraph): Both Naomi’s sons and her husband die in a famine. Ruth, one of Naomi’s widowed daughters-in-law, moves with Naomi to the latter’s home country. Ruth rejects her own pagan country to go with Naomi, pledging, “Your God will be my God and your people my people.” In the homeland, Naomi, who’s now broke and maybe even cursed, sends Ruth out to pick up scraps of wheat in a relative’s field. There, the relative, Boaz, spots her working hard and quietly. He makes sure she has food to take home. After a few days of being very impressed with her work ethic, Naomi tells Ruth that Boaz is a “kinsman redeemer,” meaning he’s a close enough relative to fulfill the Hebrew custom of a brother marrying his brother’s widow, so he can actually marry Ruth and redeem the women from their poverty. Naomi instructs Ruth to put away her mourning clothes, go into Boaz’s tent, and lie down at his feet. In the morning, he’ll propose. Ruth did as instructed. Boaz married her.

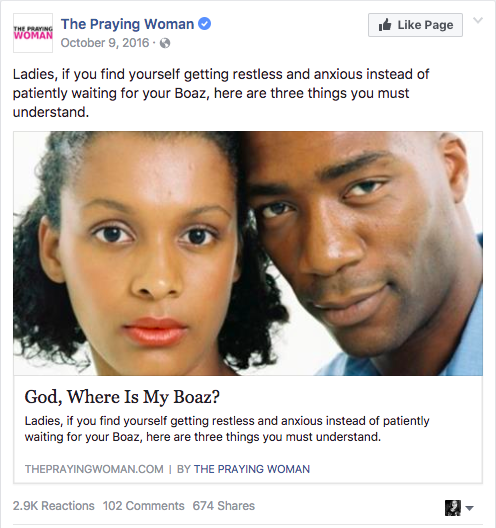

Screenshot from the Facebook page, The Praying Woman

I think almost every unmarried black church girl has told a friend or heard a friend say, “I’m waiting for my Boaz.” Women who say this learned that women who end up married to godly men who can take care of them are like Ruth. They are women who are devoted to their family and to God, who work hard and quietly at a productive activity that has nothing to do with men, and who listen to their mothers. They are not sexual. They do not waste time or money. They do not flirt. This is the embedded theology we black women carry with us as we pay for books and singles conferences that tell us how to wait, pray, take control of our desires with pure thoughts, and wait some more. I think of it as kind of an Old Testament version of a Disney princess movie. This is the embedded theology.

When Rev. Cross summarized the story as taught and said Naomi instructed Ruth to lie down at Boaz’s feet, she said, “What that means is …” I couldn’t resist finishing her sentence with, “She gave Boaz the blowjob of his life.” (H/T to Brittney Cooper for saying it in just that unforgettable way on this episode of the Unscrewed podcast.)

There were gasps in the room. The woman next to me said, “Girl, you lying!” Even people who’d been raised with affirming ideas about sex turned to me with eyes wide and mouths agape.

“Yes,” Rev. Cross confirmed. She went on to explain what a professor had explained to me and other students a few years ago in a graduate religious studies class. The word ‘feet’ used in the lie down at his feet verses is the same word used in Genesis when talking about male genitalia, so when Ruth lies down at Boaz’s feet, the text is really saying she gave him oral sex. (There was shock in the grad school class, too. After a moment of silence, one woman said, “You just ruined my favorite Sunday School story!”) Deliberative theology, then, considers Ruth and Naomi a same-sex relationship perhaps as loving as it was problematic. Naomi sent her widowed daughter-in-law to collect food scraps in Boaz’s field so they could eat, knowing Boaz would probably see Ruth and take up his responsibility as a “kinsman redeemer” to take care of her because that’s what men do in societies where widows and women without sons are among the lowest class of people. Once Boaz had noticed her, Naomi then sent Ruth to give him oral sex. (Side thought: Ruth had agreed to follow Naomi wherever she went and accept Naomi’s gods as her own, but was this what Ruth expected? I really want to know what went through Ruth’s mind when her mother-in-law said to do this.) Naomi pretty much pimped her out. It was survival sex, before marriage.

We went over a few more examples of using deliberative theology. Through this practice, instead of a pregnancy resulting from a booty call resulting from a woman parading around naked on her roof, the story of David and Bathsheba is really this. A layer is added to the story of Mary (not the mother of Jesus) hanging with the guys instead of fixing food when Jesus is teaching the Word in Mary and Martha’s house. Jesus applaud’s Mary’s decision to study. Deliberative theology is Jesus is a feminist.

What’s been interesting to me about almost every time I’ve put deliberative theology to use is that I’m looking at the same Bible, with the same words. But the patriarchal lens is lifted.

I haven’t done as much work on the next step Rev. Cross and Rev. Bev took us through: Reclaiming Truth with Affirmations. We thought about what our experience with sexuality has been and what we want it to be. Then we wrote down and told each other those positive affirmations. Death and life are in the power of the tongue, and so I wrote and spoke,

I am loved and lovable.

I live life abundantly.

I am free.

I feel most free when I dance, which was the next thing we did. I have to think more, at some point, about what dance and choreography have done for me over the years, keeping me so aware of my body, its capabilities and limitations, its beauty and what I considered its ugliness, throughout the years I was convinced devotion to God meant being divorced from carnality. In the session, the facilitators discussed how dance, or any movement we could do, reconnected mind, body, and spirit. Our brain tells us what to move when, but it’s subconscious. We move intuitively, to music with a strong drum beat. We let heart and spirit guide us. We remember that the body can be trusted. And this is healing.

Not all of this process is easy. As Rev. Cross said, “It’s hard work to be free.” It means you have to read more. Go to workshops. Spend some time alone in reflection. Figure out how to hold people you love and trust accountable for bad or incorrect teaching, or not. You risk alienation. For some, it’s safer to never reconsider anything they’ve been taught. But just this 90-minute workshop was fulfilling to me.

In the words of Rev. Bev, I leave you with this benediction:

Make peace, and make love.

Recent Comments